As I was surveying the articles and sources I intended to use to assemble this report, I realized that understanding this ecosystem means tracking the corporate giants roaming across the landscape. We’re insects on the ground beneath their feet—we need to know where they are, what they’re doing, and how they’re making decisions to both capitalize on opportunities and mitigate risks.

It’s common to take an overly anthropomorphized view of these mega-corporations. People think of them as making decisions like a person with discrete motives and consistent behavior, when they’re actually more like countries with rival factions and complex peer interactions that can’t be boiled down to a single ‘personality’. It’s like how trees compete for sunlight in the branches but connect through the same mycelial network underground. Whether two companies are allies or adversaries depends on how far you’re zooming in or out.

I’ve identified seven of the major players relevant to the Ecommerce marketing niche that I’d like to highlight.

The Seven Giants

- Google sits at the top of my map—representing Google Search, Google Workspace, Google Cloud Platform, their Android mobile OS, and hardware devices (like Pixel).

- Anthropic, moving clockwise, creates the Claude AI agent with a focus on security and safety as core development principles.

- Amazon does everything: retail, direct-to-consumer sales, plus enterprise infrastructure through AWS. They’re both a fulfillment endpoint and a marketing channel.

- Meta—Facebook, Instagram, and the broader social ecosystem—focuses on being a marketing channel, not a fulfillment endpoint. They have an audience and sell advertising to that audience as their primary business, creating relatively straightforward interactions with other companies, whether adversarial or symbiotic.

- Shopify is the other actual fulfillment endpoint after Amazon. They’re probably the most focused company here, solving one primary problem: allowing companies to sell directly to customers.

- Microsoft is another multi-headed beast. Yes, they have Bing—a significant search engine that’s only ignored relative to Google. But they’ve made major investments in OpenAI, plus they have Azure cloud infrastructure and the Office productivity suite.

- OpenAI creates ChatGPT, which has the most users so far among the major Gen-AI agents.

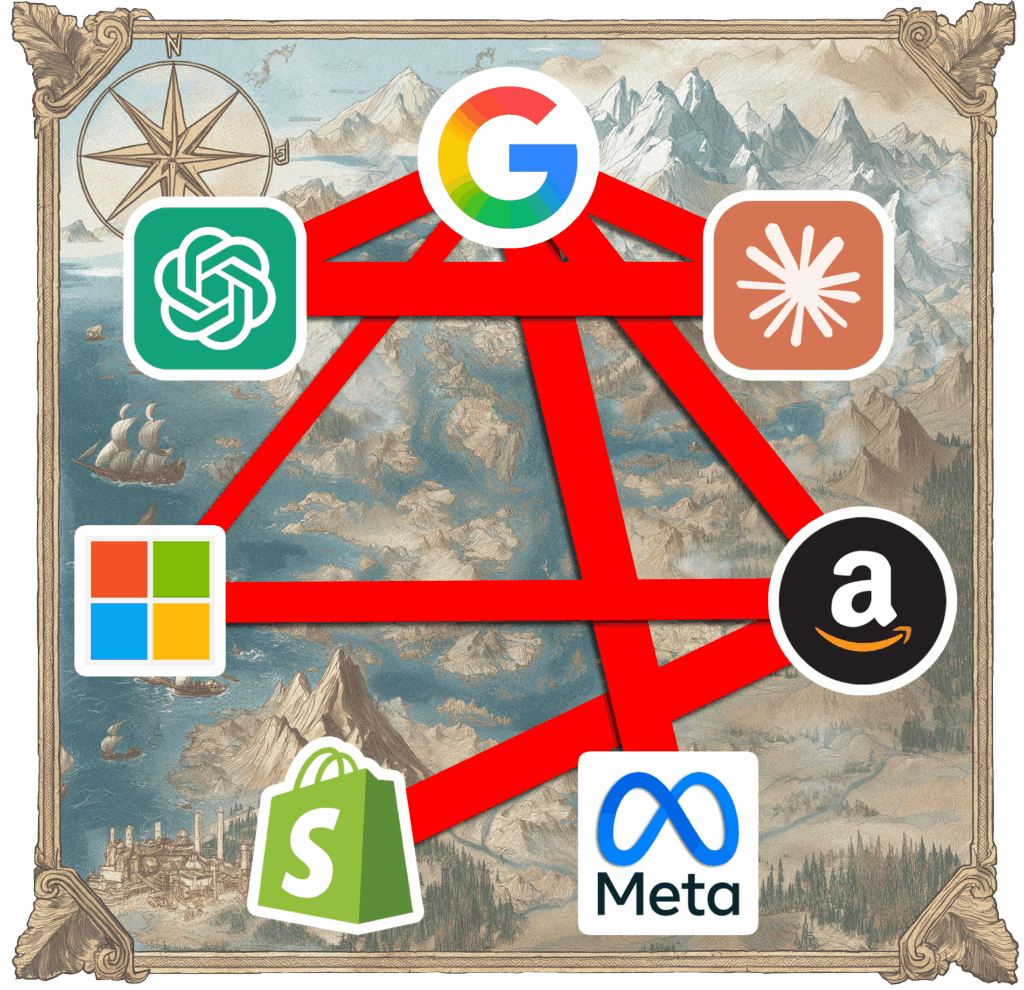

When I started this research, I expected to see hedges for every major bet or alliance—careful financial balancing that makes fiduciary sense for publicly traded companies. I wasn’t expecting lines drawn in the sand like Europe before World War I.

I found some hedging. The biggest example is Google, who heavily invests in their own Gemini while also putting $3 billion in equity and convertible notes into Anthropic and Claude. Why would Google fund a competitor to their own AI? It’s a hedge against ChatGPT, which they treat as the more existential threat.

Meanwhile Amazon has also poured capital into Anthropic, totaling about $4B, plus the fact that AWS is Anthropic’s primary cloud and Amazon Bedrock distributes Claude. This really presents two factions, each centered around major investments in AI, with Microsoft and OpenAI on one side, and Google and Amazon backing Anthropic on the other.

But what surprised me was how unhedged most positions actually are.

The Adversaries and Competitors

Some competition is obvious. Meta and Google compete for digital marketing dollars. When businesses think in terms of a fixed marketing budget (as opposed to investing proportional to anticipated return), then when someone struggles with Google, they move that budget to Facebook or vice versa.

That pits these two marketing platforms against one another for those marketing budgets.

Microsoft and Google are longtime adversaries, although the exact skirmishes have migrated over the years. Google and Bing compete as search engines, Google Workspace competes with Office and Teams. But they’re also fighting a proxy war through their AI investments. Microsoft’s $13 billion investment in OpenAI exceeds Google and Amazon’s combined investment in Anthropic. Microsoft isn’t pulling punches—they’re betting heavily on ChatGPT dominating the consumer AI space.

Amazon directly competes with Google in the long-term, strategic big picture. Both need to be the primary way shoppers seek products—the first thing you open when you need to buy something. Right now that’s the Amazon app versus Google search, but as consumer behavior changes, both companies need to maintain that go-to status in whatever new context emerges.

Amazon also competes with Google on infrastructure—AWS versus Google Cloud—and directly with Shopify as the two fulfillment endpoints where people actually exchange money for physical products.

Meta’s approach, on the other hand, is to make its LLaMA AI models widely available, almost like open-source software, while OpenAI and Anthropic keep theirs locked down and controlled. Those business model differences shape who aligns with whom, and at what levels.

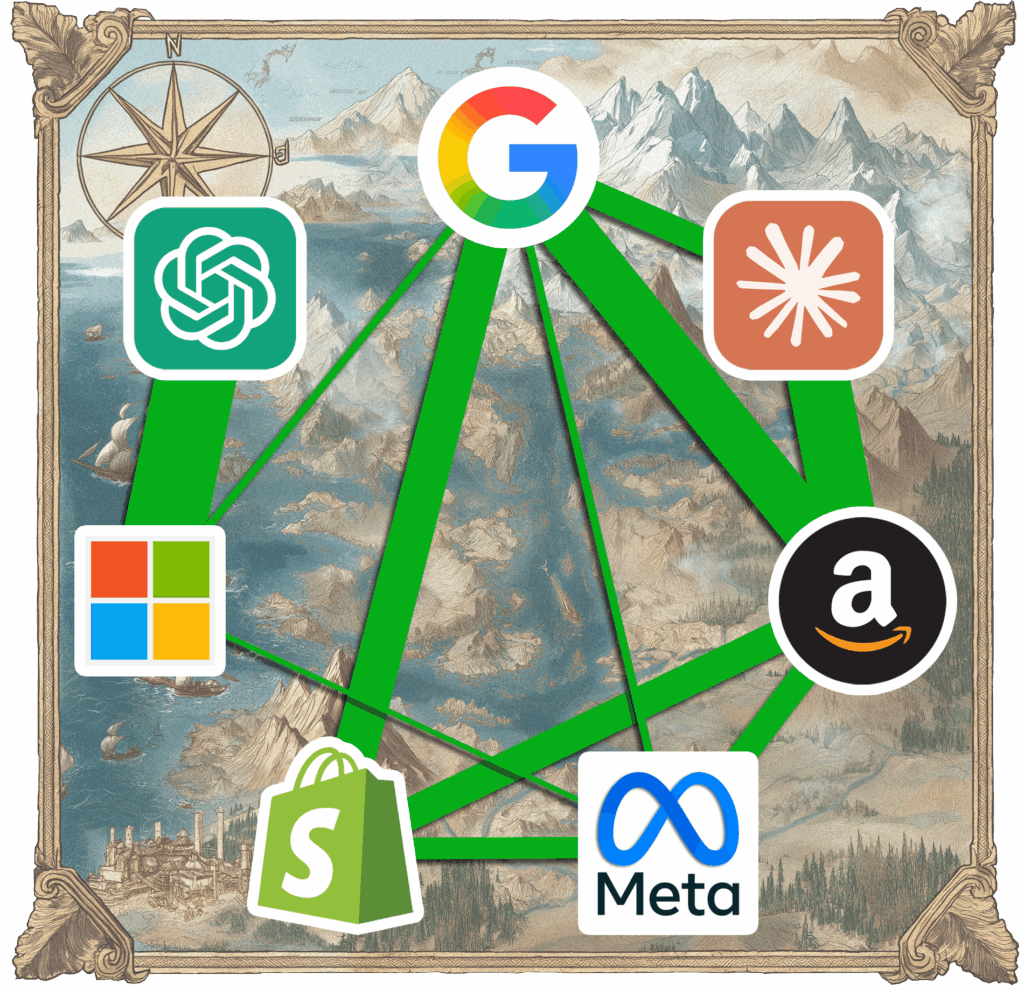

The Clients and Investment Partners

If we frame the aforementioned investments as coalitions or alliances, then we can also add in where one company is the client of another. Meta and Google, for example, obviously get ad revenue from Shopify merchants and Amazon.

Shopify and Amazon have complex relationships—Shopify merchants use Amazon as a marketplace and advertising channel, plus Buy with Prime integration.

While Amazon is Shopify’s biggest competitor for where people buy stuff, they maintain symbiotic relationships across multiple dimensions, as Shopify merchants use Amazon as a marketplace channel, plus as an advertising platform.

The Amazon vs. Google Shopping Ads Shenanigans

This brings us to what started my entire research: Amazon’s pullback from Google Shopping ads. Those with long memories remember they’ve done this before—it seemed like a power play pushing Google around and an incrementality test.

This time feels different. I think three things are happening simultaneously, but the primary goal isn’t what I initially expected.

First, yes, it’s an incrementality test. They ran it for exactly one month in all markets except the US, where it continues. By running it for a predetermined time, it sure smells like an intentionally designed test.

Second, they want leverage against Google—better advertising terms and to make their absence felt.

But here’s the third point, which I think explains the scale and continuation: Amazon isn’t trying to push Google around. They’re trying to manipulate all the other Google advertisers.

Google adapted to handle Amazon’s previous pullout and wasn’t financially impacted the way one might expect. Their financial performance is unaffected from what I could tell from their filings. They’re set up to take advantage of situations like this, especially since Google’s seen this before.

Common wisdom said Amazon pulling out would reduce auction participants, lower CPCs, and give marketers additional traffic. Some reported brief CPC drops, but I haven’t seen that in our portfolio.

The additional traffic came, but with lower conversion rates.

This reveals something interesting about Amazon’s market participation. They can profit on lower quality traffic because of their catalog breadth. They can bring in shoppers on almost any product and sell them almost anything else, giving them higher long-term conversion rates than niche advertisers who need to mostly sell shoppers exactly what they searched for.

Amazon doesn’t participate in auctions like the rest of us, exactly. They’re more like a species in an ecological niche—down in the abyssal plane gobbling up whatever opportunities drift their way, including relatively lower value, lower converting traffic that we let pass by our narrower targeting.

If you’re running Google campaigns and not paying attention to traffic quality changes, you might increase budgets to capitalize on Amazon’s absence. Who benefits? Google benefits first—advertisers who increase spend will likely maintain higher spending when Amazon returns. Then Google benefits again when another big advertiser returns, driving up bids. If CPCs didn’t drop when Amazon left, I bet they’ll rise when Amazon returns.

Amazon benefits from disrupting competitors’ marketing budget consistency. Google benefits from having those budgets handed to them.

Predicting the future is a fool’s game, but even so…

I’m willing to bet that Amazon comes back to Google Shopping in the US, too, if they haven’t already by the time I publish this.

OpenAI Takes Aim at Google

While I was working on this very article, OpenAI announced the release of ChatGPT Instant Checkout, which pits them more directly against Google and their Shopping ads.

Now, we knew this was coming in some form or another, as ChatGPT had already acknowledged that they were working on a product feed ingestion system, and we’d seen that “Orders” was included in the left navigation bar in the web interface in one of Sam Altman’s presentations.

Now we know how this is going to work, and while the details may not individually surprise you, the implications for Google could be significant. While it’s obvious that any alternative product discovery platform is at least a theoretical threat to Google Shopping and the broader Google Ads platform, the fact that OpenAI is going with a commission based fee structure is, I would argue, further eroding Google’s established marketing business, right from the foundation.

“Merchants pay a small fee on completed purchases.” – OpenAI

If you only have to pay OpenAI when they make a sale, then buying clicks from Google (while they obfuscate more and more of the underlying performance data) seems less and less reliable.

Further, they are working on a direct integration with Shopify stores, to the point that Shopify merchants don’t even need to apply to the program. It’s unclear when that will be completed, but they’re clearly sprinting to get a bite at Q4 this year.

As we’ve seen, Google searches held up just fine in the face of ChatGPT so far, but I think this may indicate a tipping point. Till now, even a conversation with ChatGPT that lead to a product recommendation still typically went to Google or Amazon to continue shopping–that could end if ChatGPT can close that last mile to the transaction! Then what might have previously been beneficial to Google (ChatGPT helping shoppers narrow in on a product) becomes OpenAI’s sharpest spear.

Strategic Implications for E-commerce

We need awareness of how this evolution continues. If Microsoft and OpenAI run away from Gemini and Claude, that encourages shoppers to use ChatGPT as a shopping mechanism, eventually eroding Google’s dominance as the starting point—and Amazon’s, since people open that app as often as Google these days.

If Amazon wins the race to be the go-to product search method, like they’ve done over the past 20 years, that draws value away from advertising on platforms like Google. Meta would still have an audience, but if people stop using Google to search, Google has no audience to sell. Google’s advertising revenue depends on people using Google as a tool, while Meta’s social ecosystems are perhaps more durable.

But there’s one company that could render this entire analysis obsolete overnight. And they’re not even on our heptagon.

While these giants fight their proxy wars through billion-dollar AI investments, Apple quietly controls the devices that most of you use to buy everything. Google pays Apple billions annually just to be the default search engine. Apple can restrict attribution data with a single iOS update, as they’ve already demonstrated.

The wildcard scenario? Apple releases a version of Siri (Apple Intelligence?) that actually works better than alternatives—an AI assistant that outperforms ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini at shopping tasks.

If Siri becomes the best way to search for products and make purchases, Microsoft’s $13 billion investment becomes worth a lot less. Google’s strategy crumbles. Amazon’s advertising manipulation becomes irrelevant.

Unlike every other player on our map, Apple doesn’t need your data to make money—they already made it when you bought the device. And like Google’s buy-in for search, Apple may just license someone else’s agent to capture that opportunity–and that may be one of the underlying motives for the coalitions forming around the major agents. In fact, right now, Siri can integrate directly with OpenAI’s ChatGPT (although it’s still a very thin integration), which is proof that they’re willing to team up with other innovators, since they haven’t really done much of that since Jobs.

One software update–and suddenly today’s map becomes a historical curiosity. I’m skeptical that they’ll pull it off, this late in the race, but it’d be foolish to ignore the possibility.

Measurement in a Complex World

Attribution and incrementality testing have become more difficult over the past decade due to privacy preference changes and regulatory scrutiny. Google and Meta both benefit from clear attribution and analytics justifying platform spending, so they’re in constant battle to maintain budget justification while Apple tries to stay out of privacy legislation crosshairs.

The trick is to stay data-driven–as long as you’re not slipping into the “trust your gut” trap, there are two approaches to planning digital marketing investments in the current landscape.

Since you can’t easily track sessions quite like we used to, attribution is difficult across devices, and people’s brains are fluid, dynamic ecosystems. Tools like Sparktoro focus on helping you find where your audience is spending their attention, giving you more opportunities to participate in their discovery process.

Depending on how you personally define what goes into “SEO,” this might be a completely revolutionary approach to doing marketing in the face of traditional SEO getting gobbled up by conversational AI product discovery. Of course, if you think of SEO as “be the most relevant result,” as I tend to, that term stretches to include this kind of proactive customer service and content development approach.

This audience-driven perspective can be used as a sort of “post-attribution” strategy, or as an excellent complement to a modern session-based attribution platform like Stiddle (disclosure: I’m an advisor) or a (very) carefully configured GA4 instance that helps you work with the data that is still available–especially for paid campaigns. Obviously tools like these still rely on you to make the data it reveals actionable, but that’s true no matter how you’re measuring performance.

Even without session-based tracking, I advocate for at least incrementality testing where it’s practical. Maybe run major campaign or channel incrementality test series once a year or quarterly, but use that to calibrate how you read platform data.

If a shopper is on both Facebook and Google—and many are—both platforms get opportunities to claim credit for a single transaction. Looking at channel reports, you’ll see two plus two equals three. When you can’t do attribution, you need incrementality testing to make budgets proportional to anticipated actual returns. Incrementality testing is the simplest way to do that—not the cheapest or fastest, but the simplest.Just as Amazon is apparently doing with their Shopping ads, you should test your assumptions and campaign contributions regularly enough to adjust strategy as this ecosystem evolves and these giants continue stomping around the landscape.

Up and to the right!